Critics never tire of reminding us that AI has no emotions, as though this were some startling revelation. Next, perhaps, they’ll inform us that penguins can’t fly and that bankers are allergic to honesty. Yes, generative AI has no emotions. But must we wheel in the fainting couches? Writers don’t need it to sob into its silicon sleeve.

Full disclosure: I am a writer who writes fiction and non-fiction alike. I am also a language philosopher; I study language. And a technologist. I’ve been working with artificial intelligence since the early ’90s with Wave 3 – expert systems. I am still involved with our current incarnation, Wave 4 – generative AI. I know that artificial intelligence has no intelligence. I also know that intelligence is ill-defined and contains metaphysical claims, so there’s that…

Meantime, let’s stroll, briskly, through three ghosts of philosophy: Saussure, Wittgenstein, and Derrida.

Saussure and the Tree That Isn’t There

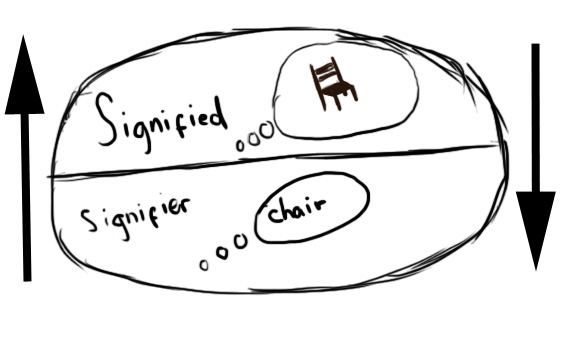

Ferdinand de Saussure gave us the tidy structuralist package: the signified (the thing itself, say, a tree) and the signifier (the sound, the squiggle, the utterance “tree,” “arbre,” “árbol”). Lovely when we’re talking about branches and bark. Less useful when we stray into abstractions—justice, freedom, love—the slippery things that dissolve under scrutiny.

Still, Saussure’s model gets us so far. AI has consumed entire forests of texts and images. It “knows” trees in the sense that it can output something you and I would recognise as one. Does it see trees when it dreams? Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Of course not. But neither do you when you define one.

René Magritte‘s famous painting reminds us that the reference is not the object.

Wittgenstein and the Dictionary Without a Key

Ludwig Wittgenstein, that glorious thorn, tore the Saussurean comfort blanket to shreds. Words, he said, are not tethered to the world with neat strings. They define themselves by what they are not. A tree is a tree because it is not a cow, a kettle, or an Aston Martin.

Take a dictionary entry:

tree

/trē/

noun

a woody perennial plant, typically having a single stem or trunk growing to a considerable height and bearing lateral branches at some distance from the ground.

What’s woody? What’s perennial? If you already speak English, you nod along. If you’re an alien with no prior knowledge, you’ve learned nothing. Dictionaries are tautological loops; words point only to more words. If you want to play along in another language, here’s a Russian equivalent.

дерево

/derevo/

существительное

древесное многолетнее растение, обычно имеющее один стебель или ствол, растущий до значительной высоты и несущее боковые ветви на некотором расстоянии от земли.

AI, like Wittgenstein’s alien, sits inside the loop. It never “sees” a tree but recognises the patterns of description. And this is enough. Give it your prompt, and it dutifully produces something we humans identify as a tree. Not your tree, not my tree, but plausibly treelike. Which is, incidentally, all any of us ever manage with language.

Derrida, Difference, and Emotional Overtones

Enter Jacques Derrida with his deconstructive wrecking ball. Language, he reminds us, privileges pairs—male/female, black/white—where one term lords it over the other. These pairs carry emotional weight: power, hierarchy, exclusion. The charge isn’t in the bark of the word, but in the cultural forest around it.

AI doesn’t “feel” the weight of male over female, but it registers that Tolstoy, Austen, Baldwin, Beauvoir, or Butler did. And it can reproduce the linguistic trace of that imbalance. Which is precisely what writers do: not transmit private emotion, but arrange words that conjure emotion in readers.

On Reading Without Tears

I recently stumbled on the claim that AI cannot “read.” Merriam-Webster defines reading as “to receive or take in the sense of (letters, symbols, etc.), especially by sight or touch.” AI most certainly does this—just not with eyeballs. To deny it the label is to engage in etymological protectionism, a petty nationalism of words.

The Point Writers Keep Missing

Here is the uncomfortable truth: when you write, your own emotions are irrelevant. You may weep over the keyboard like a tragic Byronic hero, but the reader may shrug. Or worse, laugh. Writing is not a syringe injecting your feelings into another’s bloodstream. It is a conjuring act with language.

AI can conjure. It has read Tolstoy, Ishiguro, Morrison, Murakami. It knows how words relate, exclude, and resonate. If it reproduces emotional cadence, that is all that matters. The question is not whether it feels but whether you, the reader, do.

So yes, AI has no emotions. Neither does your dictionary. And yet both will continue to outlast your heartbreak.