Film has an extraordinary talent for turning jagged, difficult novels into cultural smoothies. Hand Hollywood a text about drugs, despair, and the grotesque collapse of youth, and it will hand you back something fit for a date night. Less Than Zero was gutted. Trainspotting was diluted. Both survived, after a fashion, but only one crawled back out with its bones still rattling.

Ellis’s Less Than Zero was a flatline pulse of Californian ennui, a catalogue of hollow gestures in which the children of wealth consume themselves into oblivion. The backdrop was Reaganism in full bloom—an America drunk on consumerism, cocaine, and the fantasy of eternal prosperity. The kids in Ellis’s Los Angeles aren’t rebelling; they’re marinating in the very ideology that produced them. The film, by contrast, became a tepid morality play, complete with Robert Downey Jr.’s photogenic martyrdom. The void was swapped for a sermon: drugs are bad, lessons have been learned, and the Reaganite dream remains intact.

Welsh’s Trainspotting was messier, darker, harder to pasteurise. His junkies live in Thatcher’s Britain, where industry has collapsed, communities have rotted, and heroin fills the crater where meaningful work and social support once stood. Addiction is not just chemical but political: it is Thatcher’s neoliberalism rendered in track marks. Boyle’s film kept the faeces, the dead baby, the violence—but also imposed coherence, Renton as protagonist, a redemption arc, and that chirpy “Choose Life” coda. Welsh’s episodic chaos was welded into a three-act rave, all set to Underworld and Iggy Pop. Diluted, yes, but in a way that worked: a cocktail still intoxicating, even if the glass had been sanitised.

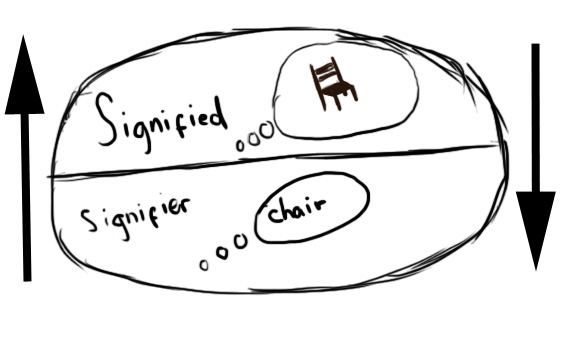

And yet, here’s the perennial fraud: drug films always get high wrong. No matter how grim the setting, the “junkie experience” is rendered as theatre, actors impersonating a template someone else once performed badly. The reality of heroin use is crushingly dull: twenty minutes of near-unconsciousness, slack faces, dead time. But you can’t sell tickets to drool and silence. So we get Baudrillard’s simulacrum: a copy of a copy of an inaccurate performance, dressed up as reality. McGregor’s manic sprint to “Born Slippy.” Downey’s trembling collapse. Junkies who look good on screen, because audiences demand their squalor to be cinematic.

And here’s where readers outpace viewers. Readers don’t need their despair blended smooth. They can sit with a text for days, grappling with jagged syntax, bleak repetitions, and moral vacuums. Viewers get two hours, max, and the thing must be purréd into something digestible. Of course, not all books are intellectual, and not all films are pap. But the balance is clear: readers wrestle, viewers swallow. One is jagged nourishment, the other pasteurised baby food.

So Less Than Zero becomes a sermon that spares Reagan’s dream, Trainspotting becomes a rave-poster that softens Thatcher’s wreckage, and audiences leave the cinema convinced they’ve glimpsed the underbelly. What they’ve really consumed is a sanitised simulation, safe for bourgeois digestion. The true addict, the tedious, unconscious ruin of the body, is nowhere to be found, because no audience wants that reality. They want the thrill of transgression without the boredom of truth.

And that, finally, is the trick: cinema gives you Reagan’s children and Thatcher’s lost boys, but only after they’ve been scrubbed clean and made photogenic. Literature showed us the rot; film sells us the simulacrum. Choose Life, indeed.